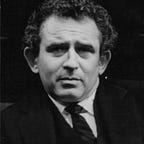

Inside Norman Mailer

By: Max Apple

I.

So what if I could kick the shit out of Truman Capote, and who really cares that once in a Newark bar, unknown to each other, I sprained the wrist of E.L. Doctorow in a harmless arm wrestle. For years I’ve kicked around in out-of-the-way places, sparred for a few bucks or just for kicks with the likes of Scrap Iron Johnson, Phil Rahv, Kenny Burke, and Chico Vejar. But, you know, I’m getting older too. When I feel the quick arthritic pains fly through my knuckles, I ask myself, Where are your poems and novels? Where are your long-limbed girls with cunts like tangerines? Yes, I’ve had a few successes. There are towns in America where people recognize me on the street and ask what I’m up to these days. “I’m thirty-tree,” I tell them, “in the top of my form. I’m up to the best. I’m up to Norman Mailer.”

They think I’m kidding, but the history of our game is speckled with the unlikely. Look at Pete Rademacher — not even a pro. Fresh from a three-round Olympic decision, he got a shot at Floyd Patterson, made the cover of Sports Illustrated, picked up an easy hundred grand. Now that is one fight that Mr. Mailer, the literary lion, chose not to discuss. The clash between pro and amateur didn’t grab his imagination like two spades in Africa or the dark passion of Emile Griffith. Yes, you know how to pick your spots, Norman. I who have studied your moves think that your best instinct is judgement. It’s your secret punch. You knew how to stake out Kennedy and Goldwater, but on the whole you kept arm’s length from Nixon. Humphrey never earned you a dime.

Ali, the moon, scrappy broads, dirty walls, all meat to you, slugger. But even Norman Mailer has misplayed a few. Remember the Chassidic tales? The rabbi pose was one you couldn’t quite pull off, but you cut your losses fast, the mark of the real pro, and I fully expect that you’ll come back to that one yet to cash in big on theology. Maybe at sixty you’ll throw a birthday party for yourself in the Jerusalem Hilton. You’ll roll up in an ancient scroll, grow earlocks, and say, “This is the big one, the one I’ve been waiting for.” With Allen Ginsberg along on a leash you’ll claink through the holy cities living on nuts and distilled water and sell your films as a legitimate appendix to the New Testament.

If I had the patience I’d wait for that religious revival and be your Boswell, then I’d drive off that whole crew of trainers and seconds who tag after you, but by then I’ll be almost fifty and maybe too slow to do you justice. As the rabbis said: “Reputation is a meal, energy a food stamp.” It’s toches affen tisch, you understand that, big boy? I’m spotting you seventy pounds, a dozen books, wives, children, memories, millions in the bank. My weapons are desperation, neglect, and bad form. I am the C student in a mediocre college, the madman in the crowd, the quaint gunman who rides into Dodge City because he’s heard they have good restaurants. We share only a mutual desire to let it all take place in public, in the open. This is the way Mailer has always played it, this I learned from you. Why envy from afar when I can pummel you in a lighted ring. Your reputation makes it possible. You who are composed of genes and risks, you appreciate the wildness of strangers. Anyway, you think you’ll mail me in one.

While I, for months, have been running fifteen miles a day and eating natural food, you train by scratching your nuts with a soft rubber eraser. You take walks in the moonlight and turn the cliches inside out. For you they make way. Sidewalks tilt, lovers quarrel. People whisper your name to each other, give you wholesale prices and numerous gifts. An “Okay” from Norman Mailer makes a career. Power like this there has not been since Catullus in old Rome carried on his instep Caesar’s daughter. I’ll give you this much: you have come by it honestly. Not by bribery and not by marriage, not by family ties and not by wealth, not by good luck alone or by the breaks of the game. You have plenty, Slugger, that I’ll admit. But I do not come at you like a barbarian. The latest technology is in my corner. The Schick 1000-watt blow-dryer, trunks by Haspel, robe by Mr. Mann, Jovan cologne, Adidas kidskin shoes travel three quarters of my shin with laces of mandarin silk. From my flesh, coated with Vaseline and Desenex, the sweat breaks forth like pearls. My desperation grows muscular in the bright lights. I am the fatted calf.

You stand in your corner like Walt Whitman. No electric outlets, cheap cotton YMCA trunks, even your gloves look used. Your read robe just says, “Norm.” You wear sneakers and no socks. I should take you the Oriental way by working your feet up to blisters and then stepping on your toes, but I lack the Chinaman’s patience. No, it will have to be head to head, although everyone has cautioned me about trading punches with you.

Last week a crowd of critics came out to my camp in a chartered bus. They carried canes and magnifying glasses. They told me to evaluate each punch from the shoulder. “Let your elbow be the judge,” Robert Penn Warren said; “Sting like an irony,” from Booth of Chicago. They told me that if I win I’ll get an honorary degree from Kenyon and a job at one of the best gyms in the Midwest. Like a Greek chorus they stood beside my training ring and sang in unison, “Don’t slug it out, move and think. Speed and reflexes beat out power. To the victor goes the victory.”

“Scram,” I yelled, spitting my between-the-rounds mouthwash. “Get lost you crummy bastards. You shit on my poems and laughed off my stories, now you want some of my body language. Go study the ambiguities of Harold Robbins.” I was mad as hell but they stood firm taking notes on my weight and reach. Finally a group of kids carrying “Free Rubin Carter” signs ran them back to the bus.

The press is no help either. They are so tired of promoting Ali against a bunch of nobodies that to them I’m just another Joe Bugner. They rarely call me by name. “Mailer’s latest victim to be” is their tag. The Times calls me a “man with little to recommend him. Slight, almost feline, with the gestures of a minor poet, this latest in a long series of Mailer baiters seems to have no more business in the ring with the master than Stan Ketchel had with Jack Johnson. No one is interested in this fight. The Astrodome will be bare, UHF refuses to televise, and Mailer has scheduled a reading for later that night at the University of Houston. Norman, why do you keep accepting every challenge from the peanut gallery? Let’s stop this Christians versus Lions until there is a real contender. Now, if the Pynchon backers could come up with a site and a solid guarantee, that might be a real match.”

You know what I say, I say, “Fuck the Times.” They gave Clay no chance against Big Bad Sonny Liston, and four years later the “meanest, toughest” champ the Times ever saw dropped dead while tying his shoes and Muhammad built a Temple for Elijah M. So much for the sports writers.

But there are a few people who understand. Teddy White will be in my corner and Senator Proxmire at ringside. The Realist and the L.A. Free Press have picked me. The DAR sent a fruit basket. Outside the literary crowd I’m actually well liked. Cesar Chavez and the migrants from South Texas are coming up to cheer for me and my friend Ira from Minneapolis and the whole English department of my school. All the Democratic Presidential candidates sent telegrams; so did Bill Buckley, Mayor Beame, Gore Vidal, Irving Wallace, John Ehrlichman, and Herman Kahn…All I can say is, when the time comes boys, I’ll be ready, just watch.

II.

Our first face-to-face meeting is at the weigh-in. He wanted to dispense with it and turn in a morning urine specimen instead. The boxing commission put the nix on that idea. Oh, he knew who I was before the weigh-in. We had traded photos, autographs, and once I had anthologized him. But face to face on either side of a big metal scale with our robes on and Teddy White rubbing my back while I stare bullets, that is something else again.

He nods, I look away. He can afford to be gracious. If I win, I’ll make a handsome donation to UNICEF in his honor. For now, I button my lip. He chats with White about convention sites, claims that because of tonight he’ll have an insider’s edge if they do the ’76 one in the Astrodome.

I come in at one hundred forty-four and three quarters, thirty-four-inch reach. He is two hundred fourteen and a thirty-inch reach. He spots me the reach and eighteen years. I give him seventy pounds and a ton of reputation. He has enough grace under pressure to teach a ballet school, but the smiles discloses bad teeth. I’ll remember that. His body hairs are graying. I can see that he has not trained and could use sleep. My tongue lies at the bottom of my mouth. “Good luck, kid,” he says, but I have removed my contact lenses and only learn later that it was the Great One in a magnanimous gesture whom I snubbed because I had to take a leak.

III.

The Dome is a half-empty cave. At the last minute they lowered all tickets to a buck, and thousands popped in to see the King. To me the crowd means nothing. It is as anonymous as the whir of an air conditioner. I stare at the Everlast trademark on my gloves and practice keeping the mouthpiece in without gagging. “Stay loose,” Teddy yells over the din, “stay loose as a goose and box like a fox.”

I dance in my corner for three or four minutes before he appears. The crowd goes wild when that woolly head jogs up the ramp. He climbs through the ropes and goes to center ring. He throws kisses with both open gloves. He is wearing the same YMCA trunks and cheap sneakers, but his robe is a threadbare terrycloth without a name. It looks like something he picked up at Goodwill on the way over. The crowd loves his slovenliness. “To each his own,” I whisper to myself as I ask Teddy for a final hit with the blow-dryer. My curls are tight as iron; his hang like eggshells crowding around his ears. He throws a kiss to me; I try to return it with the finger but my glove makes it a hand. The referee motions us to center ring. We both requested Ruby Goldstein but the old pro wouldn’t come out of retirement for a match like this one. I then asked for the Brown Bombers and Mailer wanted Jersey Joe. Finally we compromised on Archie Moore, who has a goatee now and is wearing a yellow leisure suit as he calls us together for a review of the rules. I notice that he is wearing street shoes and think to protest, but I see that he needs the black patent pumps in order to make his trousers break at the step. A good sign, I think. Archie will be with me.

He goes over the mandatory eight count and the three-knock-down rule, but Mailer and I ignore the words. Our eyes meet and mine are ready for his. For countless hours I have trained before a mirror with his snapshot taped to the middle. I have had blown up to poster size that old Esquire pose of him in the ring, and I am ready for what I know will be the first real encounter. My eyes are steady on his. In the first few seconds I see boredom, I see sweet brown eyes that would open into yawning mouthlike cavities if they could. I see indifferent eyes and gay youthful glances. Checkbook eyes. Evelyn Wood eyes. Then suddenly he blinks and I have my first triumph. Fear pops out. Plain old unabashed fear. Not trembling, not panic, just a little fear. And I’ve found it in the eyes, exactly like the nineteenth-century writers used to before Mailer switched it to the asshole. I smile and he knows that I know. Anger replaces the fear but the edge is mine, big boy. All the sportswriters and oddsmakers haven’t lulled you. You know that every time you step into the ring it’s like going to the doctor with a slight cough that with a little twist of the DNA turns out to be cancer. You, old cancer-monger, you know this better than anyone. In my small frame, in my gleaming slightly feline gestures you have smelled the blood test, the chest x-ray, the specialist, the lies, the operations, the false hopes, the statistics. Yes, Norman, you looked at me or through me and in some distant future that maybe I carry in my hands like a telegram, there you glimpsed that old bugaboo and it went straight to your prostate, to your bladder, and to your heavy fingertips. In a second, Norm, you built me up. Oh, I have grown big on your fear. Giant killers have to so that they can reach up for the fatal stab to the heart.

No camera has recorded this. Nor has Archie Moore repeating his memorized monologue noted our exchange. Only you and I, Norm, understand. This is as it should be. You have given dignity to my challenge; like a sovereign government you have recognized my hopeless revolutionary state and turned me, in a blink, credible, at least to you, at least where it counts. I slap my fists together and at the bell I meet you for the first time as an equal.

IV.

The problem now is as old as realism. You don’t want wall the grunts, the shortness of breath, the sound of leather on skin, and I don’t want to tell you in great detail. But it’s all there, the throwing of punches, the clinches, the head butting, the swelling of injured faces. If I forget to, then you put it in. For I am too busy taking the measure of my opponent to feel the slap of his glove against my flesh. The bell has moved us into a new field of force. We drop our pens. The spotlight is the glare of eternity, and what is has all come to is simply the matter of Truth. “Existentialist” I call him, spitting out my mouthpiece, though in practice I have recited Peter Piper a dozen times and kept the mouthpiece in. “Dated existentialist. Insincere existentialist. Jewish existentialist…” I hit him with this smooth combination, but he continues to rush me bearlike, serene, full of skill and power.

“Campy lightweight,” he yells, in full charge as I sidestep his rush and he tangles his upper body in the ropes. I come up behind, and as well as I can with the gross movement of the glove I pull back his head and expose the blue gnarled cacophony of his neck.

“I am Abraham and you the ram caught in the thicket,” I announce from behind. “I have been an outcast in many lands, I bear the covenant, and you full of power and goatish lust, you carry the false demon out of whose curved horn I will blow my own triumph and salvation.”

“How unlike an Abraham thou art,” he responds, gasping from his entanglement in the ropes. “Where are thy son then and where thy handmaiden Hagar, whom thou so ungenerously got with a child of false promise and then discarded into the wilderness? Thou art an assumer of historical identities, a chameleon of literary pretension.”

I reach into the empty air for the sword of slaughter when Archie Moore separates us, rights Mailer, and warns me about hair pulling and exposing the jugular of my opponent.

Now we stalk one another at center ring. He, not having trained, not having rested, not having regarded my challenge as serious, he is ready almost at once to revert to instinctive behavior. He wants it all animal now and tries to bite off his glove so that he can come at me with ten fingers. But I am still in the airy realms of the mind. I see and discern his actions. How coarse appears the Mailer saliva upon his worn gloves, how disgusting his tongue and crooked teeth as they nibble at the strings. His mouth has become as a loom with the glove lace moving between his teeth on the slow, feeble power of his tongue.

“The Industrial Revolution,” I yell across the ring, and his gloves drop, his mouth is open and agape. I land a hard right to his jaw and feel the ligaments stretch. At the bell he is dazed and hurt. He moves to his corner like an old man in an unemployment line.

I stand in the middle of the ring and watch the slow shuffle toward comfort of this man whom most enlightened folks thought I could not withstand for even three minutes. So carefully have I trained, so honest has been my fifteen miles of daily roadwork that the first round of exertion has scarcely left me breathless. While Norman is in his corner swishing his mouth, having his brow mopped, I am in mid-ring, stunned with my opening achievement. I have stayed a full round with him. I have seen the fear in his eyes and the beast in his soul. I have felt the heft of his sweating form in a heavy embrace. In the clinch, as our protective cups clicked against each other, there have I surmised his lust. For three metaphysical moments we two white men have embraced in violence while old black Archie pares his perfect fingernails in the midst of us.

“Don’t forget the game plan,” Teddy is yelling from my corner. He wants my help in pulling the blackboard through the ropes. I come out of my reverie to help him. Oh, I have been waiting for this moment, and now but for good old Teddy I might have forgotten. Like the most careful teacher printing large block letters for an eager second grade, I inscribe and turn to four sides so all can see, “The Naked and the Dead Is His Best Work.”

When Norman reads my inscription, he is swishing Gatorade in his mouth while his second, Richard Poirier, applies with a Q-tip glycerine and rosewater to the Mailer lips. When by barb registers, he swallows the Gatorade and bites the Q-tip in half. Poirier and Jose Torres can barley keep him on his stool. They whisper frantically, each in an ear. Archie is across the ring getting a quick shine from a boy who manages, on tiptoe, to reach with his buffing cloth up to the apron of the elevated ring. Arch kneels to tip with an autograph.

When the bell tolls round two, I face a Mailer who has with herculean effort quickly calmed himself. He has sucked in his cheeks for control and looks, for the moment, like a tubercular housewife. I see immediately that he has beaten back the demiurge. We will stay in the realms of the intellect. His gloves are completely laced and his steps are tight and full of control. He dances over to the ropes and beckons me with an open glove to taste his newness.

Who do you think I am, Norm? Didn’t I travel half a world with no hope of writing a book about it to watch Ali lure George Foreman to the ropes? Not for me, Norm, is your coy ease along the top strand. I’ll wait and take you in the open. You see, I learned more than you did in Africa. While you holed up in an air-conditioned hotel and resurrected those eight rounds for your half a million advance, I thumbed my way to what was once called Biafra. I went to the cemetery where Dick Tiger lies died of causes unknown at age thirty-five in newly prosperous Nigeria. How did you miss Dick Tiger? You who were the first white negro, you the crown prince of nigger-lovers, you missed the ace of the jungle. Yes, he was the heart of the dark continent, the Aristotle of Africa. A middleweight and a revolutionary. While you clowned around with Torres and Ali and Emile Griffith, Tiger packed his gear and headed home to see what he could pick clean from the starvation and the slaughter. He went home to face bad times and bad people and was dead a week after his plane touched down. Where were you and the sportswriters, Norm, when Dick Tiger needed you? I at least made the trek to the resting place of the hero, and it was there in the holy calm of his forgotten tomb that I vowed to come back and make my move. No one offered me a penny for “The Dick Tiger Story” as told to me, so you won’t get it now either. Come out to the middle, Norm. No, you’re still coy, relaxed; well, two can play that one.

I sit down in the corner opposite him; I fan myself with the mouthpiece. To the audience it looks as if we’re kidding. He sloping against the ropes, I twenty-five feet away pretending I’m at a picnic in the English countryside. Real fight fans know what’s up. There is only a certain amount of available energy. In the universe it’s called entropy; in the ring it is known as “ppf,” punches per flurry. Neither of us has the strength at this moment to muster the necessary ten to twelve ppf’s to really damage each other. Fighters trained in the Golden Gloves or various homes for juvenile delinquents will go through the motions anyway. They will stalk and butt and sweat upon each other. But Mailer and I, knowing the score, wait out the round. Archie Moore leafs through the Texas Boxing Commission rules. Some fans boo, others take advantage of the lull to refresh themselves.

For me, every second is a victory. Round by round I wear the laurel and the bay. Who thought I could even last the first? Five will get me tenure, seven and I’ll be a dean. Yes, I can wait, Norm, until you come to me in mid-ring with all that bulk and experience. Come to me with your strength, your wisdom, your compassion, and your insight. This time at the bell we are both giggling, aware each to each of the resined canvas upon which we paint our destines.

I walk over to his corner where he sits on his stool, kingly again, not hurt as he was after round one. He offers me a drink from his green bottle. We spit into the same bucket. I know his seconds don’t like me coming over there between rounds. Poirier turns away but Norman smiles, cuffs me playfully behind the neck. Together we walk out to await the bell.

For twice three minutes we have traveled the same turf. Ambition and gravity have held us in a dialectical encounter, but as round three begins, Mailer’s old friend the irrational joins us. No matter that I actually see the pig-tailed form of my sister beckoning me between mouthfuls of popcorn to rush at you. Aeneas, Hector, Dick Tiger, they too saw the phantoms that promise the sunshine and delight after one quick lunge. My sister is nine years old. She wears a gingham dress. She is right there beside you, close enough for Archie to stumble on.

“Watch out kid,” I say, “you shouldn’t even be here.”

“It’s okay,” Mailer says. “She has my permission.”

She throws the empty popcorn box over the ropes. “Please take me home,” she whimpers, and as she stands there the power enters me, the ppf quotient floods my own soul, and I rush, not in fear, not in anger, but in full sweet confidence, I rush with both fists to the middle of Norman Mailer.

First my left with all its quixotic force and then my sure and solid right lands in the valley of his solar plexus. Next my head in a raw, cruel butt joins the piston arms. Hands, arms, head, neck, back, legs. As a boy for the first time shakes the high dive in the presence of his parents, with such pride do I dive. And with the power of falling human weight knifing through the chlorine-dark pool do I catapult. As a surgeon lays open flesh, indifferently, thinking not of tumors but of the arc of his racquet in full backswing, with such professional ease am I engulfed. I hear the wind leave his lungs. Like large soft earlobes, they shade me from the glare of his heart. The sound of his digestive juices is rhythmic and I resonate to the music of his inner organs. I hear the liver weakened from drink but on key still, the gentle reek of kidneys, the questioning solo of pancreas, the harmonica-like appendix, all here all around me, and the cautionary voice of my mother: “Be careful, little one, when you hit someone so hard in the stomach. That’s how Houdini died.”

Somewhere else Archie Moore is counting ten over a prone loser. Judges are packing up scorecards and handbags snap shut. I am comfortable in the damp prison of his rib cage. His blood explodes like little Hiroshimas every second.

“Concentrate,” says Mailer, “so the experience will not be wasted on you.”

“It’s hard, “ I say, “amid the color and distraction.”

“I know,” says my gentle master, “but think about one big thing.”

I concentrate on the new edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica. It works. My mind is less a palimpsest, more a blank page.

“You may be too young to remember,” he says, “James Jones and James T. Farrell and James Gould Cozzens and dozens like them. I took them all on, absorbed all they had and went on my way, just like Shakespeare ate up Tottel’s Miscellany.”

“No lectures,” I gasp, “only truths.”

“I am the Twentieth Century,” Mailer says. “Go forth from here toward the east and earn your bread by the sweat of your brow. Never write another line nor raise a fist to any man.” His words and his music are like Christmas morning. I go forth, a seer.

Max Apple has published two collections of stories, two novels and two books of non-fiction. His memoirs, Roommates was made into a film as were two other screenplays. His stories and essays are widely anthologized and have appeared in Atlantic, Harpers, Esquire, and many literary magazines. He has received grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities, The National Endowment for the Arts, and the Guggenheim Foundation. His Ph.D. is in 17th century literature. He has given readings at many universities. He spent most of his teaching career at Rice University where he held the Fox Chair in English.

“Inside Norman Mailer” was first published in The Georgia Review 30.2 (Summer 1976), 278–289. Reprinted with permission of the author and with Thanks to Justin Bozung.