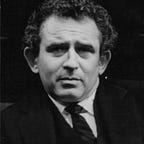

Portrait of Picasso as a Young Man

An Interpretive Biography

By Chris Busa

Stocky, powerful, and libidinous, he was also short, cowardly, and fearful. A rough chunk of primal matter, with dark zones of energy drawn around the eyes, he mesmerized women. He mesmerized men. For the artists who came of age during the ’30s and ’40s, Norman Mailer’s generation, Picasso was God. Mailer witnessed this homage and absorbed it, eventually signing a contract in 1962 to write a biography of the artist and spending some weeks with Picasso’s oeuvre in reproduction and two more months writing a series of self-interviews. These inquiries were essentially dialogues between self and soul about the violent act of creating artistic forms.

Published in 1966 as a 200-page conclusion to Cannibals and Christians, a collection of occasional pieces, the writing was all the more extravagant for being in the bastard form of journalistic Q&A. Mailer explored his key ideas through the dynamic of an interrogator who was at once sympathetic and hostile, pushing the argument forward with either a pull from the front or a kick in the behind, here with invigorating encouragement, there with questions so challenging as to be damning. A generative concept for Mailer was that “form was the physical equivalent of memory,” meaning that the form, say, of a piece of driftwood revealed the history of the wood. The scars and missing knots, knobs and hollows, were evidence of its experience. Its very deformities were telling and embodied time in the same way that Cubism, by splaying separate planes onto a flat surface, put past, present, and future into a single dimension. Additionally, if terrors were part of the history of the form, then the form possessed the power of a gargoyle and cound function magically to protect the creator from the anxiety it expressed. Mailer expected his mediation to function as a midwife to his imagination in producing the project biography, but he found, as he says in the preface to the book finally delivered last year, 30 years later, that Picasso “had stimulated the dialogues in such a way that one had insights into the extremities of one’s own thinking but few biographical perceptions about him.”

Why did it take Mailer so long to develop the biographical perceptions offered now? How could it be otherwise? The occasion to imagine Picasso as a young man had to wait until Mailer was an old man, partly, no doubt, because of the tremendous research involved in mastering the drama of Picasso’s growth as an artist. In his robust voice, Mailer shows why mistresses of ten start out as models and are discarded when they no longer serve the muse. Mailer brings out Picasso’s artistic competitiveness, his sexual jealousy (Picasso would no more let his mistress model for other artists than he would allow them to put a stroke on his work in-progress), and his clairvoyant regard for the tyranny of his own hand-eye condition. Hundreds of Picasso’s works are reproduced, the photographs woven into the text as in a well-timed slide presentation. Mailer’s descriptions of Picasso’s paintings and drawings are full and convincing, a model of how to saying something important about visual art and say it without the tedious jargon of the expert. And, keeping in mind that Mailer never met Picasso, one could compare Mailer’s portrait to those of several biographers of Picasso, including John Richardson, Francoise Gilot, and James Lord, and maintain that Mailer’s book is as vivid as those by his intimates. It is true Mailer has been criticized for quoting abundantly from primary sources, but it is obvious that a work of scholarship would not be competent without a utilization of established references. Indeed Mailer translates several of the sources himself, and what would be an editorial coup for an obscure scholar becomes the failing of a major author. The real resentment must arise from knowing that Mailer worked with material available to all, yet was able to animate it by refracting it through his own consciousness.

As a 19-year-old Spanish painter in Paris, Picasso could not speak French, but he learned, as Mailer says, that the curve of a line proved to be the equal of a turn of phrase. This link between the visual and verbal is the fulcrum of Mailer’s insight into Picasso. Mailer discusses a portrait of Casagemas, Picasso’s friend who committed suicide in late adolescence. In this small oil, 11 by 14 inches, a thick, phallic candle burns beside Casagemas in repose under a sheet, his bearded face exposed to a lurid flame. Mailer is not the first to remark that the flame, its brightness gaping from within, looks like a vagina, even as it seems to mean something luminous about the boundary between life and death. The early work hints at Picasso’s future process, through psychological description to rough, primitive, carved expressions of form, and Mailer says, “it could be argued that there will be a direct line of development over the next decade from the Blue Period, soon to appear, into the vast aesthetic range of Cubism. Picasso had entered the world of visual equivalents.”

Mailer continues, “One can ponder the concept. An artist’s line in a drawing can be the equivalent of a spoken word or two. The bend of the fingers can prove equal to a ‘dejected hand,’ or the outline of the upper leg muscles speak of an ‘assertive thigh.’ Form is also a language, and so it is legitimate to cite visual puns — that is, visual equivalents, and visual exchanges. No matter how one chooses to phrase it, artists, for centuries, have been painting specific objects, only to discover that they also look like something else.”

Picasso was born during an earthquake. He was witness to an autopsy of a woman killed by lightning, performed with a saw on her skull in order to examine her brain. Picasso was himself the groundbreaker who split the faces of the women he loved, dividing by dissection, deforming savagely, and doubling the face by exposing the profile. Mailer writes of the portraits of Olga, Picasso’s first wife, his mistress Dora Maar, and his second wife, Jacqueline, that “we can see that he lived, nonetheless, with these women in a manner that some men can never do: He was in each relationship — he saw the women as his equal. No matter how hideously he presented these three women, he would never have delineated them so if he had not entered into a depth of revulsion for what their relationship had become, and that, in turn, disclosed how hideous were his own spiritual sores. The physiognomy of his psyche is present in each of these portrayals.”

Mailer’s portrait focuses on Picasso as a young man as he undergoes the profound transition into the creator of “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon,” and an important portion of the book — leading through the urchin melancholy of the Blue Period and the opium-like bliss of the Rose Period and through the cubist collaboration with Braque — is told through the eyes of Fernande Oliver, Picasso’s first serious mistress with whom he lived for seven crucial years, 1905–1912, in the bohemian squalor of the dilapidated “Bateau Lavoir” in Montmartre. “A strange and sordid house,” she writes of their residence, “the most diverse noises sounding from morning to night, discussions, songs, exclamations, cries, the racket of slop pails being emptied and dropped to the floor, the noise of pitchers being set down on the stone of the fountain, doors slammed, and the most questionable groans which passed right through the closed doors of these studios.” Large portions of her second set of memoirs, never published in English, have been translated by Mailer, and her voice, so present in feeling, sustains Mailer’s running commentary on space and time, form and creativity.

Mailer’s probing instinct for the motives, noble and base, that drive the great artist might seem to offer the famous author an opportunity to expound on his own motives, but, no, Picasso’s egotism is an occasion for Mailer’s modesty. The book’s strength is that its author does not compete with his subject — could Mailer as a young man have been as modest? Mailer seems to make no assertion, however provocative, that cannot be substantiated by a discussion of some work of Picasso’s. My favorite is the idea that the cubist search for universal form may have been driven by the desire to transcend sex. “Not all love affairs are carnal,” Mailer writes. The four-subject portrait that is “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” was never resolved by Picasso. The artist could not satisfy himself. One feels in the dichotomies of the painting the tortured blending of the rock-like manliness of Gertrude Stein and witch-like femininity of Fernande. Mailer’s meditation on form thus leads him to meditation on gender, inspired by Gertrude Stein, whom he says represents “the most monumental crossover in gender” that Picasso had ever encountered. With Fernande, Picasso “had entered the essential ambiguity of deep sex, where one’s masculinity and femininity is forever turning into its opposite, so that a phallus, once emplaced within a vagina, can become more aware of the vagina that its own phallitude — that is to say, one is, at the moment, a vagina as much as a phallus,or for a woman vice versa, a phallus just as much as a vagina: At such moments, no matter one’s physical appearance, one has, in the depths of sex, crossed over into androgyny.”

Reprinted with permission from Provincetown Arts Magazine, Volume 12, 1996, pp. 116–118.